Ron's Story

LSU, Guatemala, Penn State, US Army

Chapters

LSU, fall 1964 - spring 1968 |

Guatemala, summer 1968 |

Penn State Grad. Sch., fall 1968 |

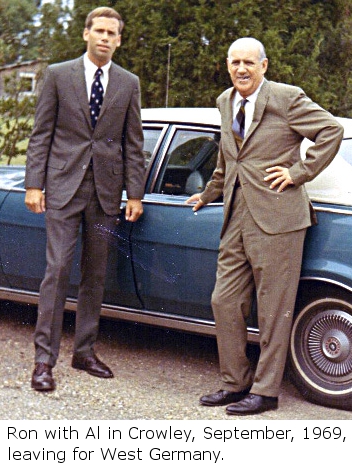

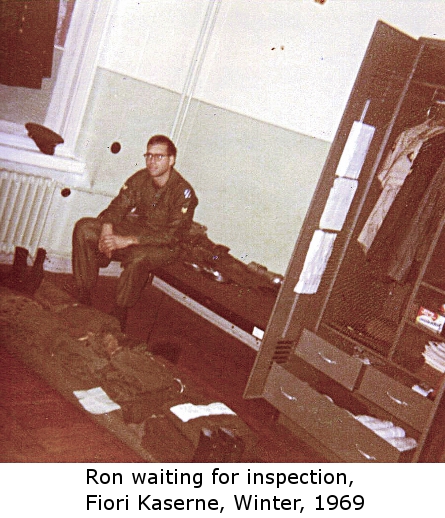

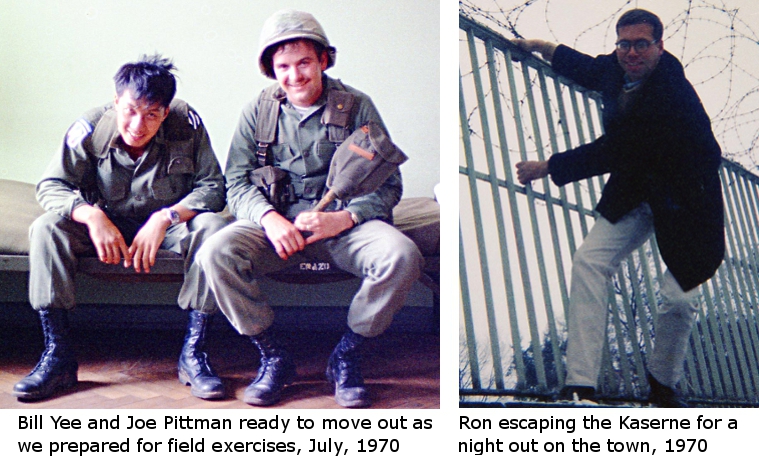

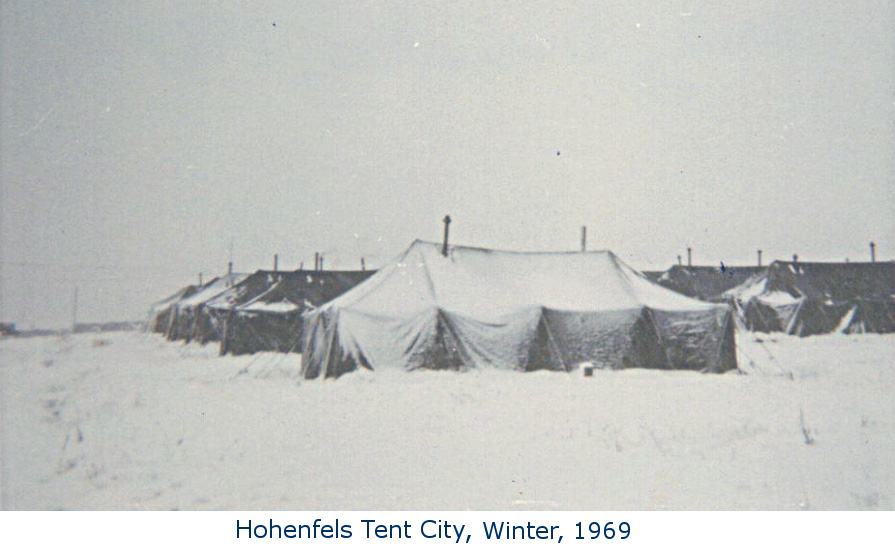

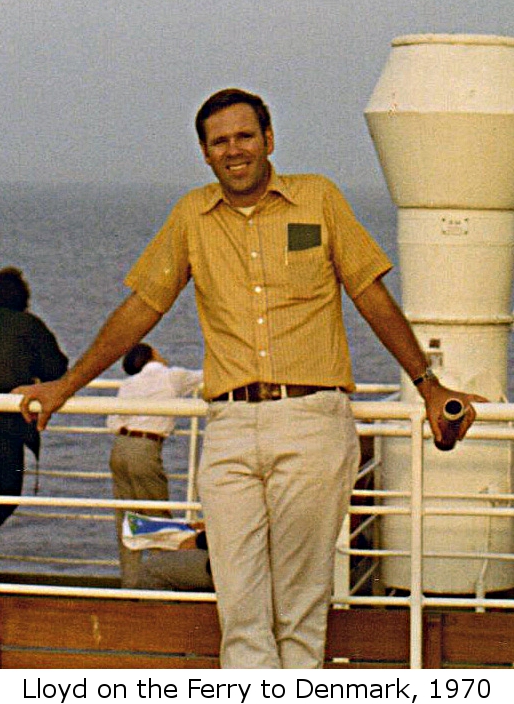

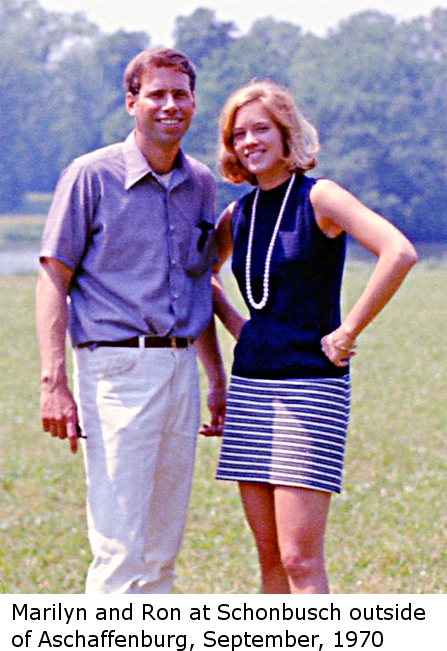

US Army, fall 1968 - fall 1970 |

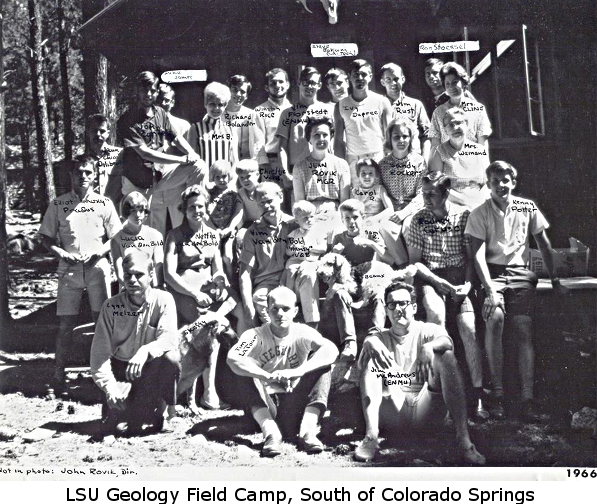

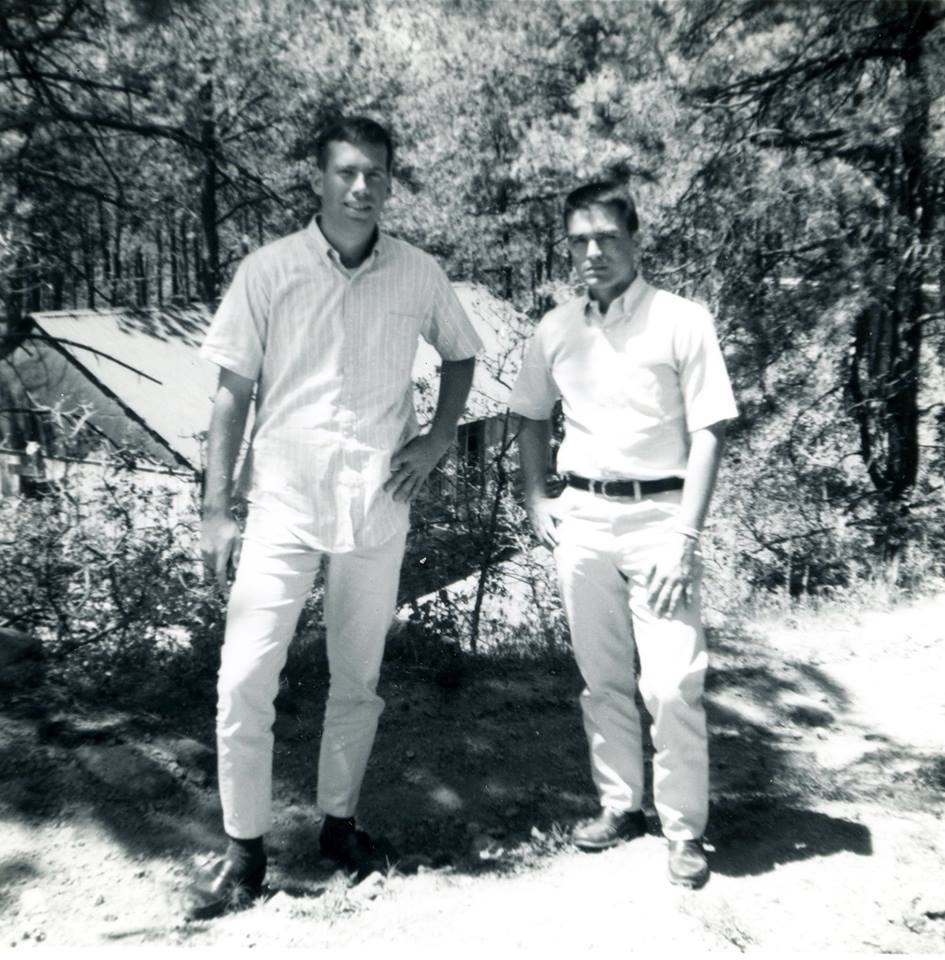

LSU, fall 1964 - spring 1968 |

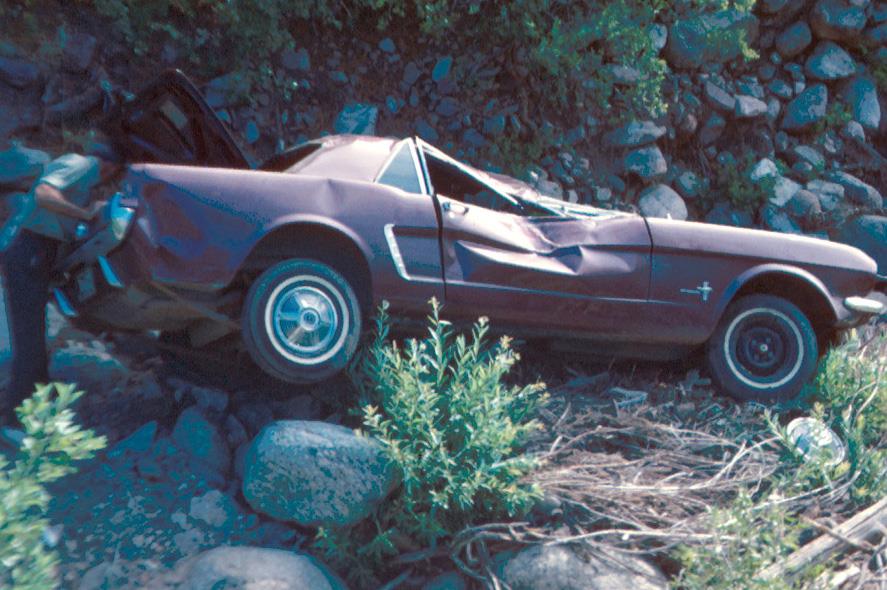

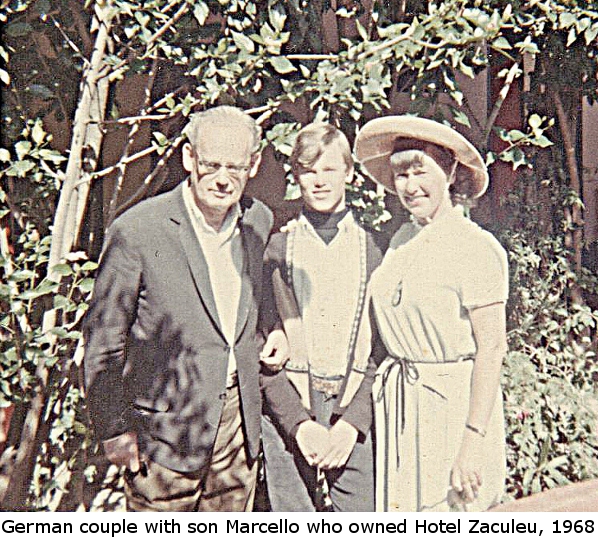

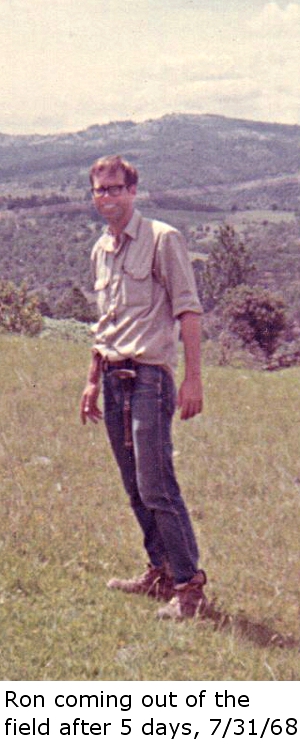

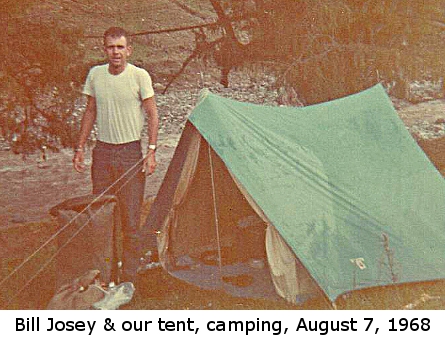

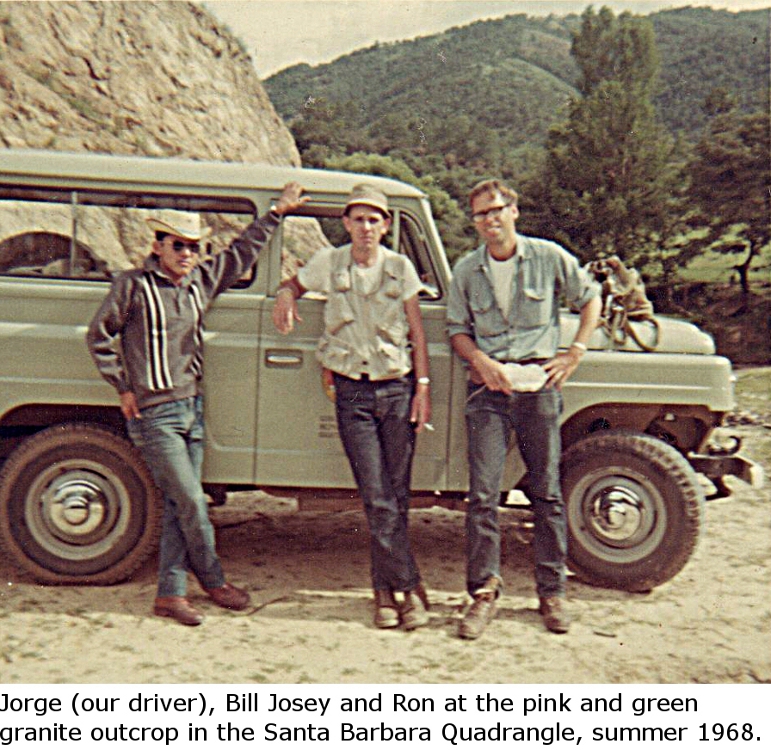

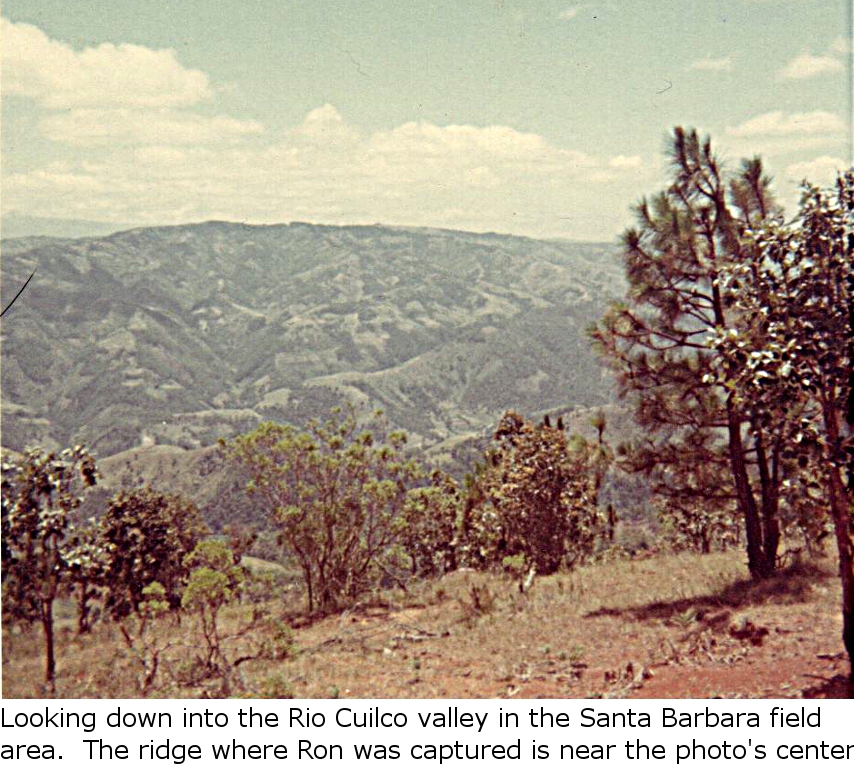

Guatemala, summer 1968 |

Penn State Grad. Sch., fall 1968 |

US Army, fall 1968 - fall 1970 |